Credits and references

- Victor Farcic

- More elaborate unattributed Google Code archive

Incremental Kata - no peeping ahead!

This is an incremental kata to simulate a real business situation: work your way through the steps in order, but do not read the next requirement before you have finished your current one.

Your Task

You’re part of the team that explores Mars by sending remotely controlled vehicles to the surface of the planet. Develop an API that translates the commands sent from earth to instructions that are understood by the rover.

Requirements

- You are given the initial starting point (x,y) of a rover and the direction (N,S,E,W) it is facing.

- The rover receives a character array of commands.

- Implement commands that move the rover forward/backward (f,b).

- Implement commands that turn the rover left/right (l,r).

- Implement wrapping at edges. But be careful, planets are spheres.

- Implement obstacle detection before each move to a new square. If a given sequence of commands encounters an obstacle, the rover moves up to the last possible point, aborts the sequence and reports the obstacle.

Rules

- Hardcore TDD. No Excuses!

- Change roles (driver, navigator) after each TDD cycle.

- No red phases while refactoring.

- Be careful about edge cases and exceptions. We can not afford to lose a mars rover, just because the developers overlooked a null pointer.

Facilitation notes (warning, spoilers)

There are multiple solutions for the requirement of “wrapping around the edges”. Depending on the background of your participants, they might have different understandings of the coordinate system. Previous experience doing this kata shows that misunderstandings, e.g. participants arriving with different mental models, can easily derail the kata and deflect from testing and designing. For facilitators, we recommend you work towards the participants aligning on which model to go by.

It is most helpful to work with visualizations and spend some structured time exploring the problem and the options the participants present and highlight how they can all be valid solutions.

Torus/Donut: Retaining euclidian geometry

Similar to games (think snake, pacman), where the player vanishes on the top and reappears on the bottom (vis versa for left & right), this might be a solution someone with a mental model based in maths/topology or games arrives at.

The implementation does not produce any new edge cases, but the mental model might be hard to align on.

Example:

In a 4x4 grid (x ∈ { 1, 2, 3, 4 }, y ∈ { 1, 2, 3, 4 }) the following table shows the resulting position for a movement on the grid:

| Initial Position \ Operation | x + 1 | x - 1 | y + 1 | y - 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1, 1) | (2, 1) | (4, 1) | (1, 2) | (1, 4) |

| (2, 1) | (3, 1) | (1, 1) | (2, 2) | (2, 4) |

| (2, 2) | (3, 2) | (1, 2) | (2, 3) | (2, 1) |

| (3, 1) | (4, 1) | (2, 1) | (3, 2) | (3, 4) |

Credit to @drpicox for providing an explanation for this model.

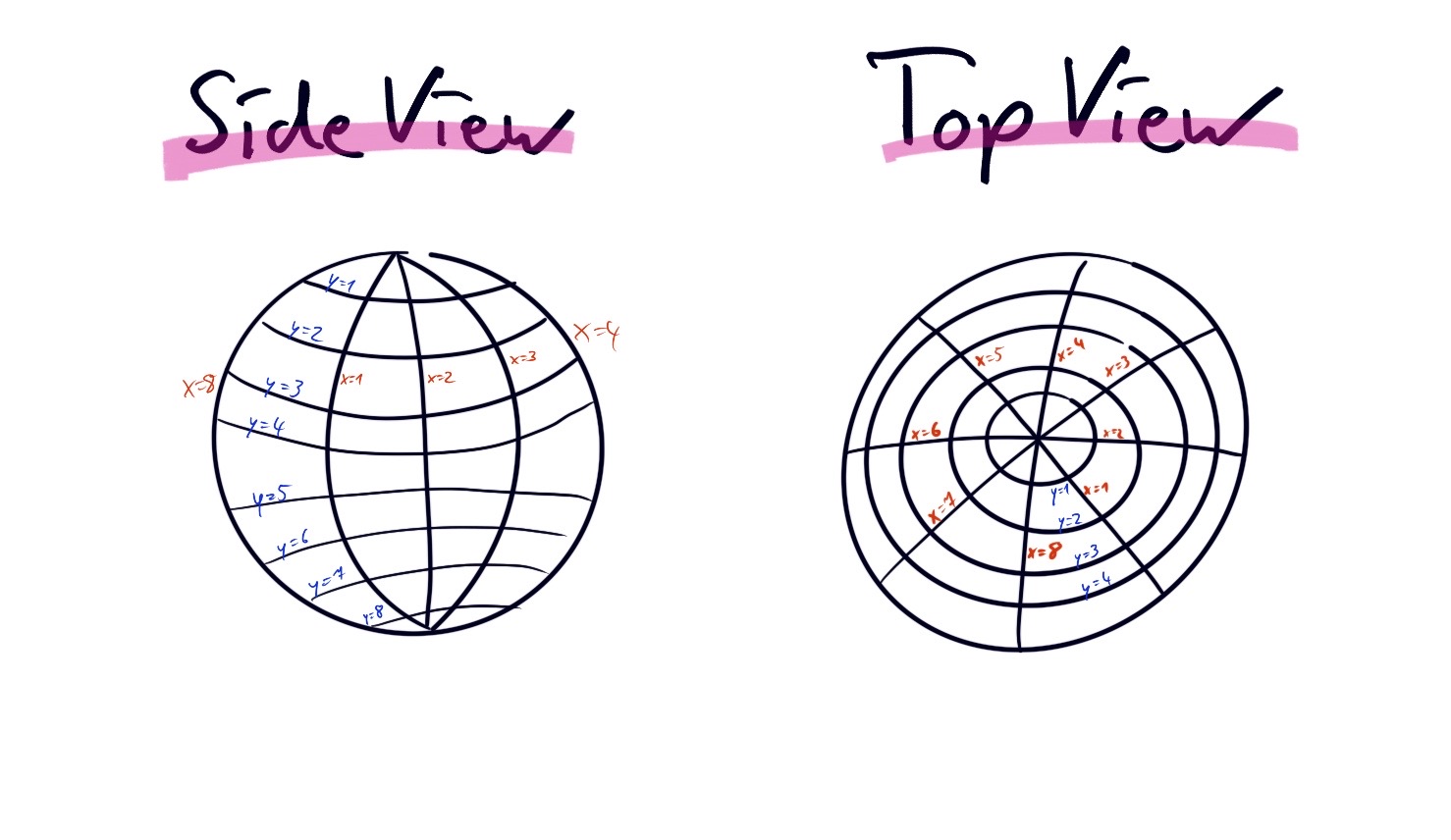

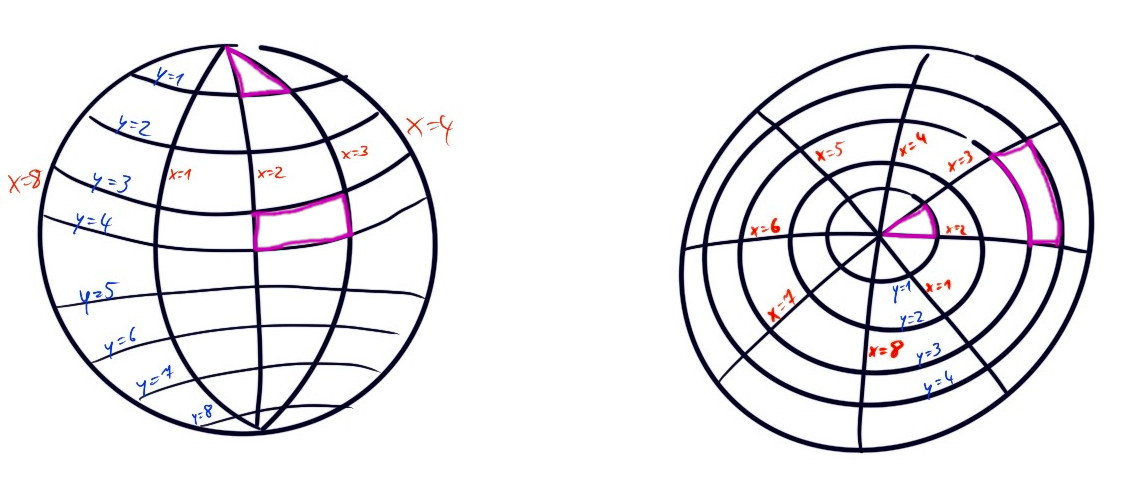

Polar coordinate system: Thinking in maps and planets

This interpretation of the grid system lends itself to the concept of latitude and longitude. The sphere is sliced into an even number of latitudes (equidistant lines) and longitudes (evenly spaced lines from North to South pole)

In this model, X and Y become abstract representations of longitudes and latitudes.

While the model might be the first one people arrive at if they’re coming from the mental models of planets and maps, it produces some significant edge cases that make this solution rather challenging:

Some potential challenges:

- The distance between two points of the grid is no longer the actual distance. (two points close the poles are closer to each other than two points on the equator)

- If the Poles can be represented through the coordinates, the behaviour at that point is undefined. E.g. at the North pole, the Mars Rover always faces South (by definition), but the direction it would move forward to is informed by the longitude it is facing. (e.g.

(x, 1)for allx ∈ {1, 2, 3, 4}describes the same point, but a different point the mars rover will end on if it moves forward.) - The geometry at the poles is no longer euclidian, e.g. the path you take at the pole to arrive back at the same position has three corners, where everywhere else it has four.

This interpretation is vastly more complex, but can be tamed by constraining the solution to the following aspects:

- The number of latitudes and longitudes is the same and a multiple of 2

xandyare positive integers. Positions not on the grid can not exist.- The poles are not “on the grid”. The rover moves “over” the pole but never rests on them.

Example

In a 4x4 grid (x ∈ { 1, 2, 3, 4 }, y ∈ { 1, 2, 3, 4 }) the following table shows the resulting position for a movement on the grid:

| Initial Position \ Operation | x + 1 | x - 1 | y + 1 | y - 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1, 1) | (2, 1) | (4, 1) | (1, 2) | (3, 1) |

| (2, 1) | (3, 1) | (1, 1) | (2, 2) | (4, 1) |

| (2, 2) | (3, 2) | (2, 1) | (2, 3) | (2, 1) |

| (3, 1) | (4, 1) | (2, 1) | (3, 2) | (1, 1) |

Starting Points

Clojure, CoffeeScript, C++, C#, Erlang, Groovy, Intercal, Java, JavaScript, Lisp, PHP, Ruby, Scala

Image credits

Image by Egga. It shows an exemplary flip chart to facilitate the kata.